Two things have impressed me greatly here in southern Sweden, particularly in the province of Blekinge: rocks, and trees. The farmland here is characterized by being interspersed with rock outcroppings, the very bedrock of this country exposed to the elements. Most fields are surrounded by low stone fences, rocks collected over centuries and piled by the side of the field to separate one pasture or cultivated plot from the next.

Throughout the forests one encounters these fences, some four or five feet high and hundreds of years old, no longer partitioning a farm but reminding us that unless one labors diligently the forest will overtake the land and return it to its original condition.

Surrounding the Naval Shipyards in Karlskrona is a high stone wall which still protects the area from intrusion. The only way to see this historic site is by guided tour on a boat from the water side. Sweden has built warships here since the early 1700’s and continues today with ultramodern vessels. But the rocks still stand guard.

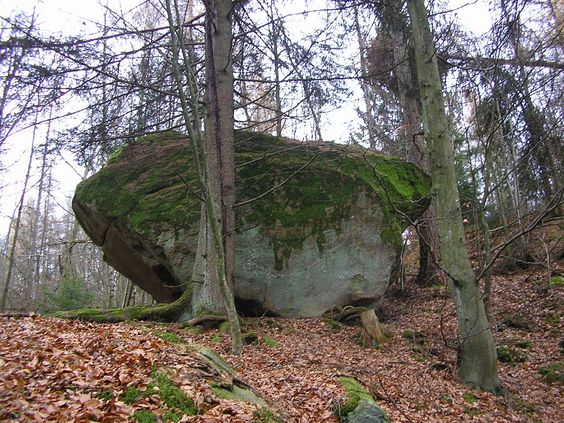

Sometimes a stone is too large to move, glacial erratics they are called, having been carried for miles by glacier ice then dropped in place as the ice receded. The farmer simply plows around them. In other places the bedrock itself is in the way, the shallow soil creeping up to it. Such an outcrop may be in the middle of the field, with a few oak trees trying to eke a living out of cracks in the stone. Other fields, more recently converted from forest to cultivation, still have numerous smaller rocks that will have to be gathered and moved to the outskirts of the field.

And Swedes have used stone for centuries as a building material. Here are the ruins of an old castle called Lyckå Slott, built about 1560 when this part of Sweden belonged to Denmark, and abandoned about 1600 and mostly dismantled. It is built in the Danish style with uncut stones cemented together and was originally a two story structure with two towers at opposite corners.

Even the streets and walkways are still made of stone, not the rounded cobbles of centuries past (although they are still encountered), but square-cut blocks set in a bed of sand.

As we drive along the highway every few miles the roadway cuts through this bedrock. It was a Swede, after all, that invented dynamite. I get the sense that we are seeing the bare bones of this ancient land. And what a strong, sturdy, solid foundation it is. From these bones of stone has risen a people of intelligence with a sense of community, a people that seeks to care for the welfare of the weak and believes strongly in equality for all. I think some of their political approaches to the problems of society are misguided, but that does not negate my respect for their genuine concern for all humanity.

“God left the world unfinished for man to work his skill upon. He left the electricity in the cloud, the oil in the Earth. He left the rivers unbridged and the forests unfold and the cities unbuilt. God gives to man the challenge of raw materials … not the ease of finished things. He leaves the pictures unpainted and the music unsung and the problems unsolved … that man might know the joys and glories of creation.” -Thomas S. Monson

And now sticks, or I should say, trees. The forests here are impressive. There is evidence of centuries of cultivation, management and stewardship of the forests. In fact, as my friend Klaus says, Sweden is forest. I love the tall pine trees reaching up – they grow slowly here because of the shorter growth season so far north and limited sunlight for half the year. This leads to a denser, stronger timber.

I love the birch trees, singly or in stands, graceful with long, fine branches and the loveliest green in the spring and summer, and gold in the fall. The stark white trunks when the leaves have fallen off are beautiful. As they age the trunk becomes darker and almost black, but the young trees are my favorite.

And then the oak: Blekinge province is noted for its abundant oak trees; in fact, the county coat of arms bears a stylized oak tree as its symbol. They do not usually form thick groves like the birch, pine or spruce but stand in more isolation. The older ones grow thick and gnarly. For some reason their branches continually change direction over a short length of growth, so that they seem disjointed and crooked and remind me of old Disney cartoons of characters walking through a spooky forest.

Many of these trees can be found near old farm houses and some are of tremendous girth, evidence of their great age. They are like the good spirits of the farm, guarding the inhabitants and families for generations and watching over them and giving shelter from the sun with their leaves in the summer and giving roost to the birds throughout the year.

Back in the 1600’s Swedish warships were built from the abundant oak trees in the area, and realizing the importance of the oak to this enterprise it was ordered that all the oak trees belonged to the king. It takes several hundred years for an oak to grow to the size where its timber can be used to build a warship. It was only recently that an adviser to the king advised, “Sire, your oak trees are now old enough to harvest!”